On Tuesday, Minnesota released results from the 2025 Minnesota Student Survey (MSS). The data offer a mixed picture: signs of recovery in engagement and mental health, paired with troubling trends in attendance. They also reveal challenges for the survey itself, with participation rates continuing to decline.

Given every three years, the MSS offers a comprehensive, statewide look at things that matter deeply to students and families, like engagement, safety, mental health, and social development. The survey is one of the only tools we have to elevate student voices collectively, as statewide data points. Adults should feel an obligation to take these results seriously.

This post reviews key findings—and ends with what Minnesota must do next to improve the survey and protect our ability to hear from youth.

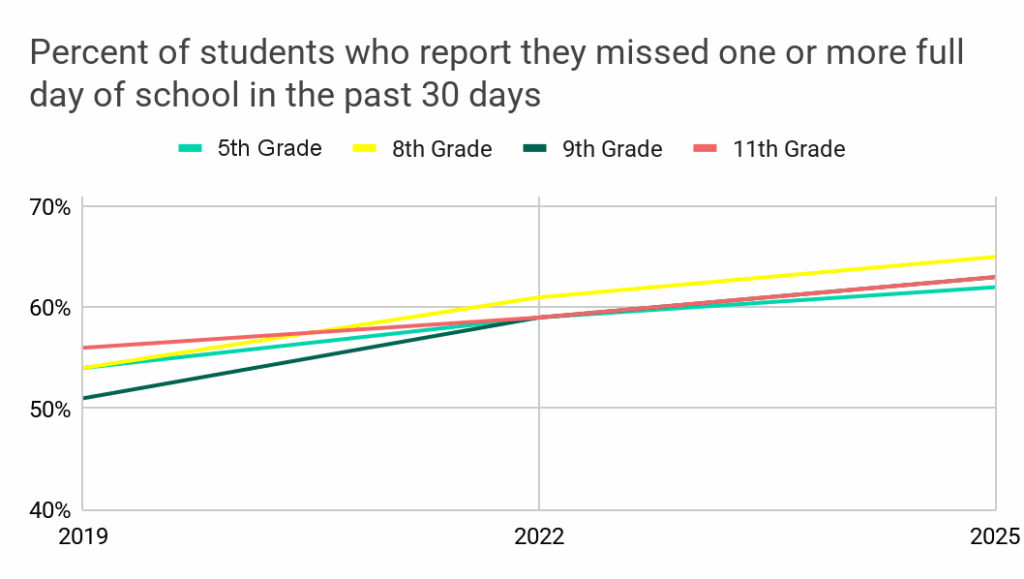

Attendance: Students Report a Growing Challenge

The percentage of students who report missing one or more full days of school in the last month continues to rise—and even exceeds the 2022 rates.

Across grades, the reasons students report for being absent are familiar. In approximate order (though the exact order varies among grades) the top five are:

- Feeling sick

- Health-related appointments

- Being out of town

- Not getting enough sleep

- “Did not want to go”

These results echo the chronic absenteeism crisis nationwide—though interestingly, this self-reported student data show less improvement than recent state attendance data suggest. In other words, from students’ perspectives, absenteeism may be worsening, not resolving.

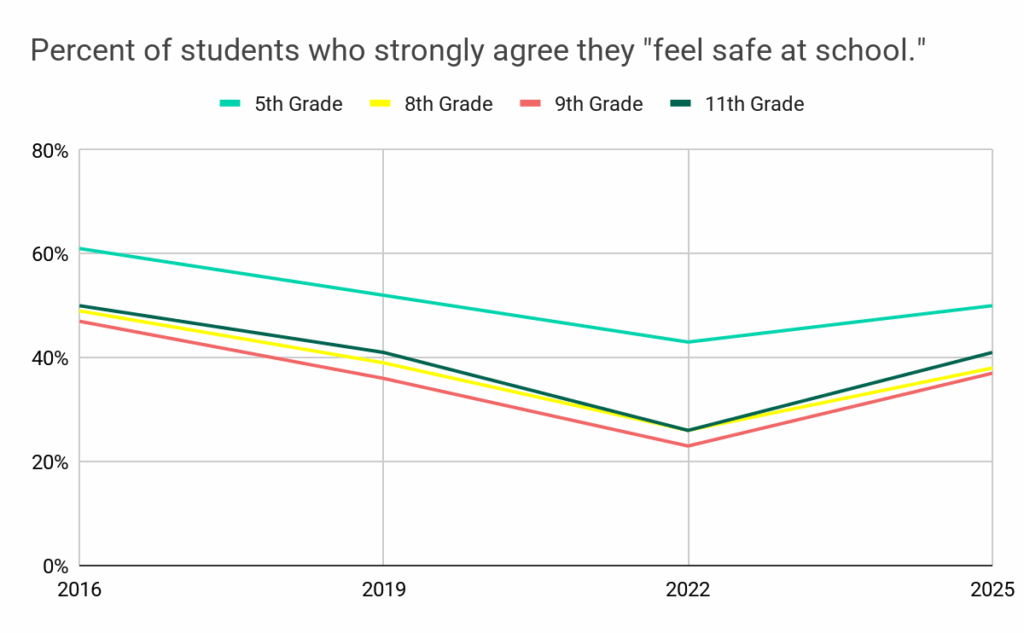

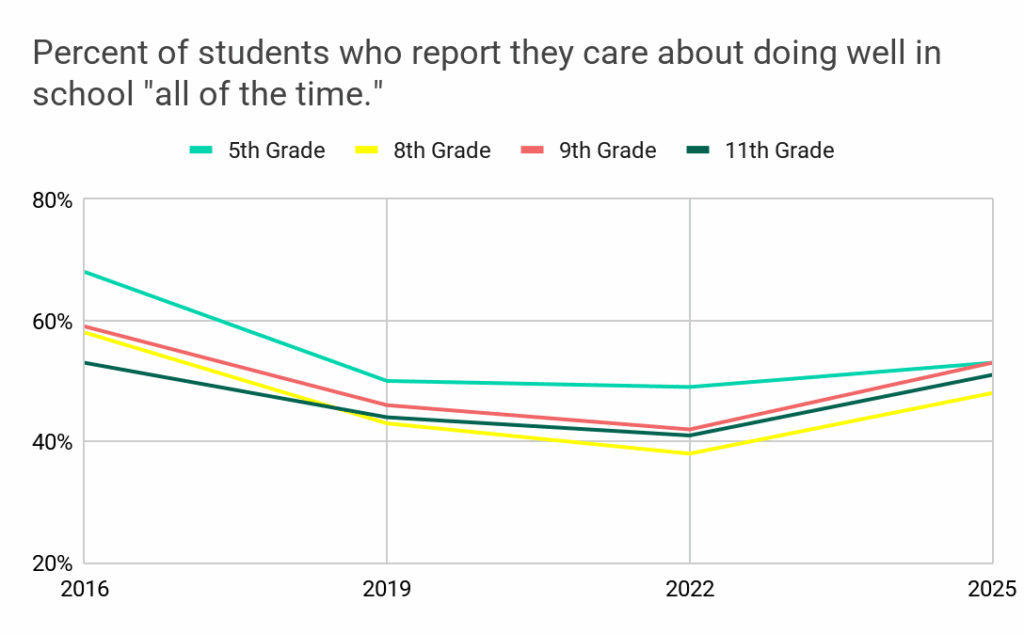

Sense of Safety and Engagement: Signs of Reconnection

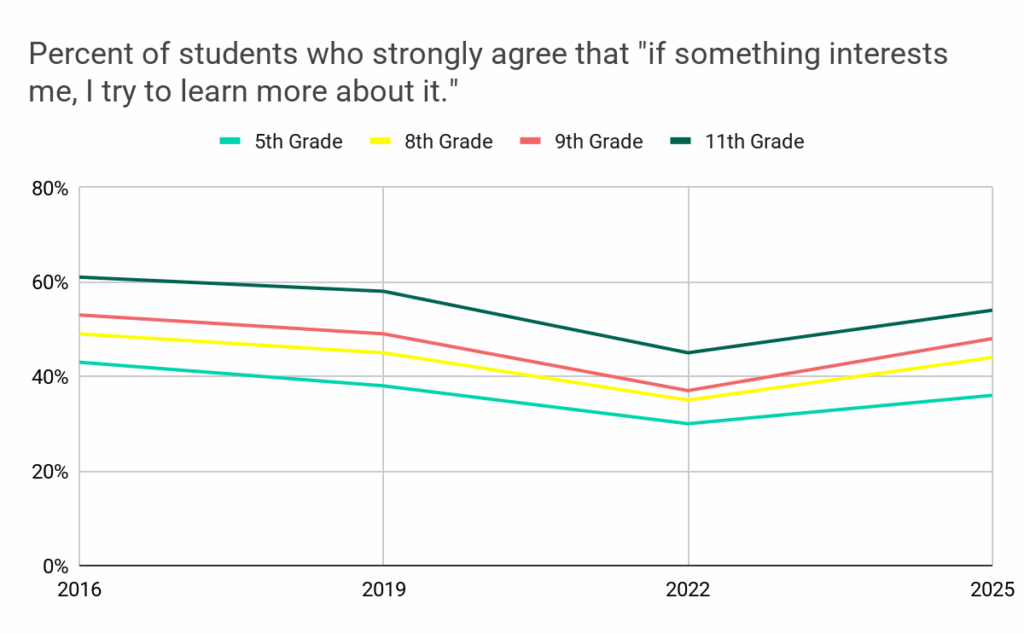

Indicators of student engagement and positive experiences in school show improvement across grades—recovering from low points in 2022. Students are more likely than in 2022 to report feeling safe at school, caring about doing well in school, and actively engaging in their education.

While some gains are modest in size, they are not trivial in meaning. They reflect a system slowly rebuilding relationships and routines disrupted by the pandemic.

They also track a notable shift in the relationships students report with teachers. For example, the percent of 11th graders who say teachers care about them “very much” or “quite a bit” jumped from 36% to 49% between 2022 and 2025—with “very much” answers alone doubling from 8% to 19%.

When students feel known and cared for, engagement improves. And here we see one of the clearest hopeful signals in the new data: students are feeling better connected to adults.

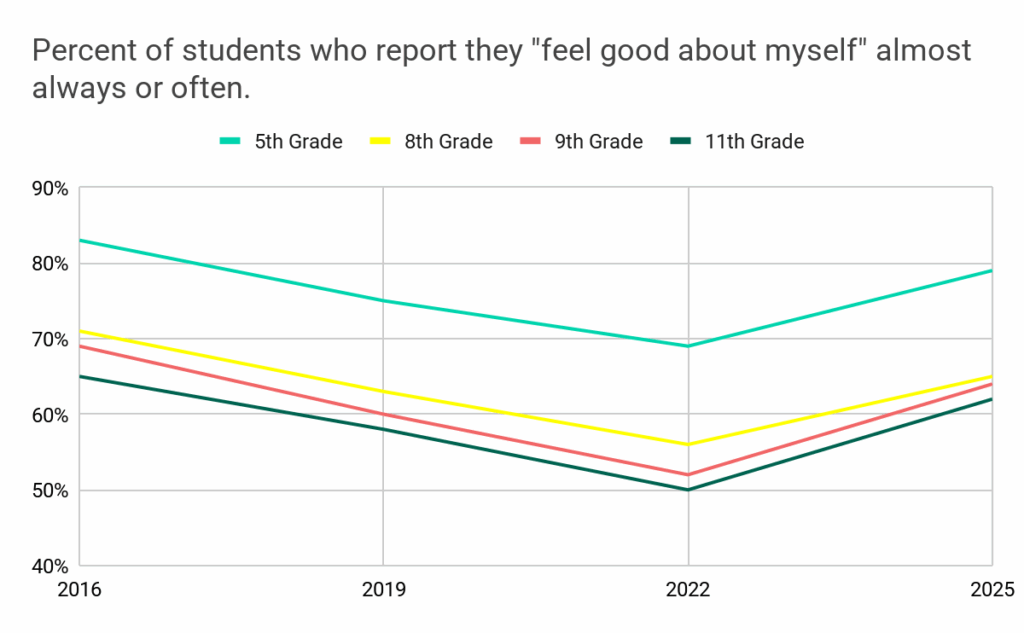

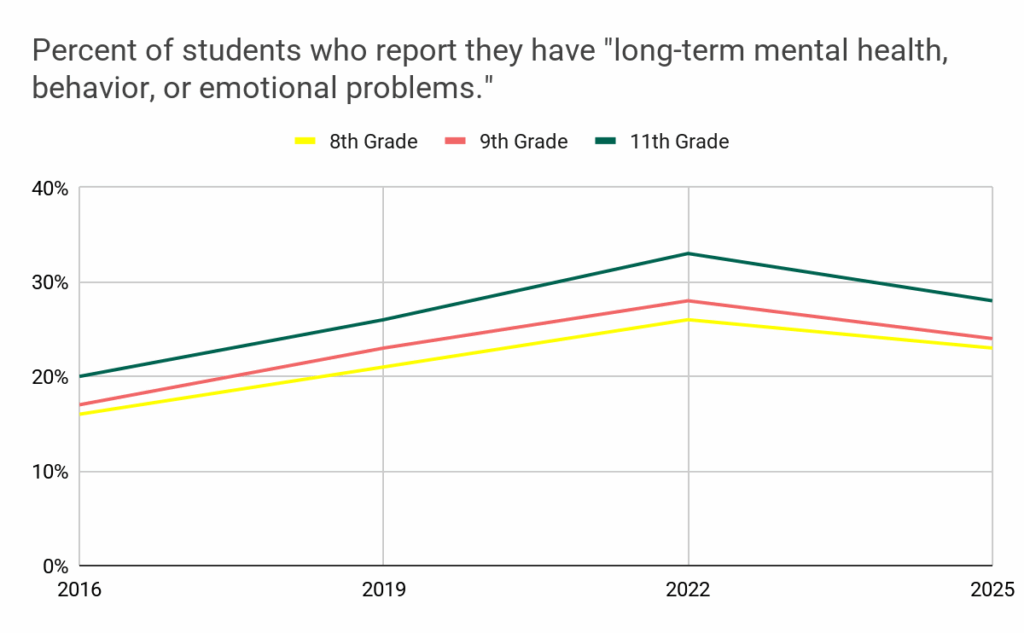

Mental Health: Gradual Recovery, With Persistent Severity

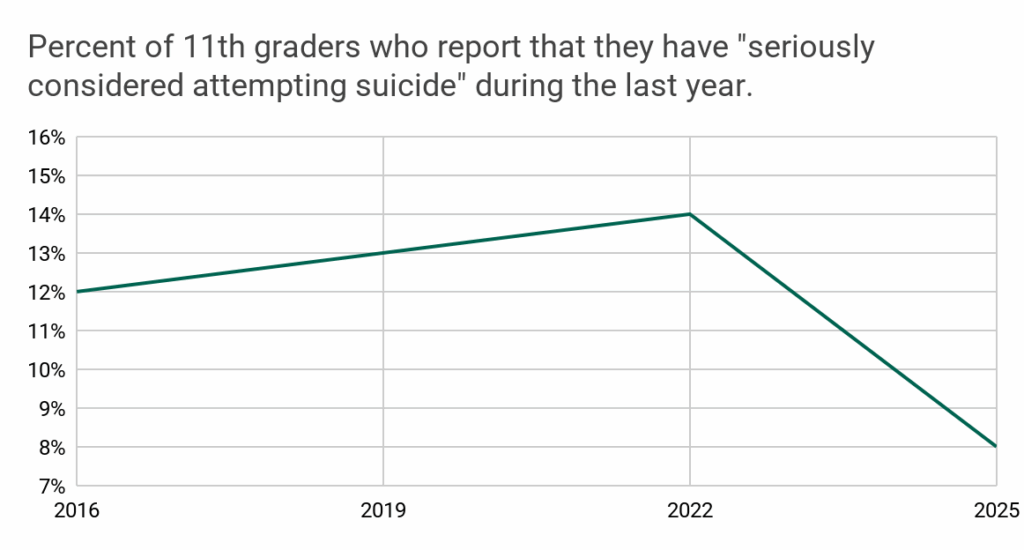

Youth mental health remains a serious challenge, though the 2025 results point toward gradual healing. Students are more likely to say they feel good about themselves and experience fewer long-term mental health challenges. Even the most extreme indicators—considering or attempting suicide—show improvement.

While these are encouraging shifts, the numbers remain staggering and tragic. Even improved numbers reflect thousands of Minnesota youth facing thoughts of self-harm. We have a responsibility to reflect on these findings with deep sincerity.

Inequities By Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Sexual Orientation

While statewide averages are useful for understanding overall trends, they can also obscure persistent inequities. When results are disaggregated by gender, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation (the groups for whom data is publicly available) the MSS reveals stark differences in student experiences—differences that reflect long-standing education inequities in Minnesota.

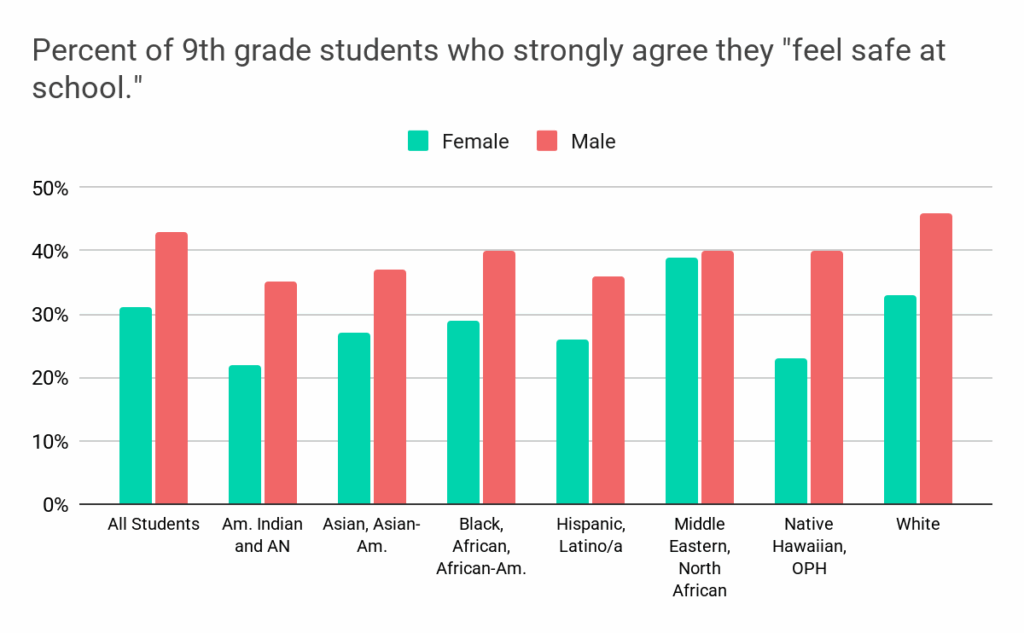

For example, on the question of students feeling safe at school, the percentage of students who strongly agree—and who identify as American Indian/Alaska Native and female—is half that of White male students. Other patterns and inequities are visible in the chart below.

Other questions on engagement and motivation vary substantially by gender across all racial groups. For example, while the percentage of 11th grade students who strongly agree they “care about doing well in school” is 60% among female students, only 41% of male students report the same.

Public data also disaggregate results by sexual orientation, where grave realities emerge in questions about mental health. For example, while the percent of all 11th graders who report “seriously considering suicide” was 8% statewide, that rate is more than double—just shy of 20%—for students who are gay, lesbian, or queer.

This analysis only begins to surface the inequities revealed when data are disaggregated. It’s critical that schools and districts look closely at their own results—particularly for the student groups they serve—and dig deeper to understand these disparities and dismantle the conditions that sustain them.

The Survey Itself: Crucial, But Participation Declining

One particularly concerning trend in the data is not related to youth—it’s the participation in the survey itself. Over the 10 years since the 2016 administration, district participation has fallen from 85% to 61%, and student participation from 68% to 45%.

If this trend continues, Minnesota risks losing one of the most comprehensive, student-centered data tools it has.

If districts, schools, and students don’t see value, participation will continue to fall—and the survey will not survive.

In the interest of preserving the MSS—and making it work even better for youth—Education Evolving published in 2023 a paper with conclusions and recommendations. Several common themes emerged from dozens of interviews with students, teachers, district leaders, county officials, and researchers:

- The survey’s purpose is muddled for those to whom it most needs to be clear. Researchers report it is useful; school leaders and educators less so.

- Many educators couldn’t recall what the survey measures, how they would use it, or frankly that it even exists.

- Ultimately, the MSS is losing out to shorter, annual surveys that offer schools and districts quick, clear, actionable data.

In short: if districts, schools, and students don’t see value, participation will continue to fall—and the survey will not survive.

Looking Ahead: A Modern Youth Survey System for Minnesota

It would be easy to carry on as usual and get started on the 2028 survey administration. But this year could and should be a turning point—a moment to reconsider the survey’s purpose, design, and future.

What must happen next? We must walk several paths in parallel:

First, build the case for the survey. Other states have coordinated campaigns that clearly explain the value of their surveys. Minnesota needs consistent, proactive messaging, and coordinated supporters—especially to counter misinformation and help educators, families, and students see how the data supports better learning and well-being.

Second, improve the survey itself. Every item needs a hard look: what purpose it serves, who uses it, and whether it still belongs. The total number of questions must come down. Some questions can be given to a sample of students, not all. Survey design must meaningfully involve students and educators. All of this would be more possible with a consistent budget item or appropriation.

Third—and most boldly—offer a new annual survey. A shorter (~40 items or less) survey should capture the most important selection of items schools and districts use to plan and improve. It would also serve as a widely-used survey platform onto which the full MSS could be “tacked onto” during every third year, thus simultaneously boosting participation in the full MSS.

Over two-thirds of all states use this twin-survey model to sustainably elevate the voices of their youth. Minnesota should too.