The latest data show that less than half of Minnesota students (49%) read proficiently. That’s ten points down from a decade ago, a downward trend that started in the late 2010s and only accelerated post-pandemic. The READ Act seeks to turn things around.

But some literacy instruction experts worry Minnesota may fall short of the Act’s objectives if we fail to hold students to high expectations and engage them in materials they find relevant and meaningful.

We spoke to leaders at the Network for the Development for Children of African Descent (NdCAD)—whose longstanding literary instruction programs buck the state’s slipping scores—to hear what lessons they would share. But first:

What’s in the READ Act?

Passed in 2023, the READ Act requires schools to provide “evidence-based reading instruction” focused on foundational reading skills. That means instruction that emphasizes phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension—core components of what’s called “the science of reading.”

These components are backed by decades of cognitive science and represent the most effective way to ensure students learn to read words accurately and fluently.

The Act requires districts to:

- Provide specific training and ensure reading interventions are made by trained teachers.

- Administer reading screeners to all students grades K-3.

- Develop and adopt formal plans for how they’ll have all students reading at or above grade level.

The law addresses some crucial gaps—and sets a high bar for schools to clear. But there’s a risk of reducing literacy to technical proficiency if relevance and meaning get left out of the equation.

Lessons from an integrated, culture-centered approach

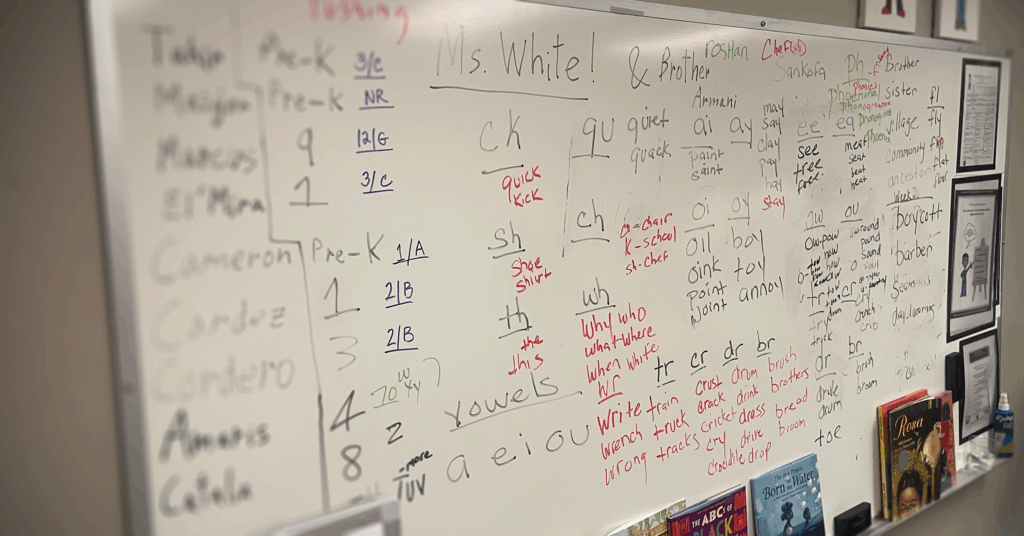

[NdCAD’s programs] include all the core components of the science of reading—but through a culture-centered, or integrated, approach.

Since 1997, experts at NdCAD have honed literacy instruction programs that include all the core components of the science of reading—but through a culture-centered, or integrated, approach.

Now, “culture-centered” does not mean “the science of reading with a cultural flavoring.” Nor is NdCAD’s integrated approach an alternative to the science of reading—but a powerful extension that makes it stick. NdCAD founder and executive director Gevonee Ford explains.

“[Our approach] is integrated into a larger endgame [which] is, ‘I understand why reading is important. It’s important because it helps me succeed in school. But it also helps me understand who I am. And who my family is. And who my community is. And my responsibility and place in the world.’”

2025 NdCAD Summer Training Institute

August 18-19

Broaden how you think about education, reading instruction, and strategies to ensure all children succeed in school and life. For parents, teachers, early childhood providers, school administrators, and more.

The Sankofa Reading Program at NdCAD serves K-8 students in afterschool and summertime settings. Sankofa students make critical connections between reading and cultural identity development through culturally-specific texts, individual learning plans, and complementary “Parent Power” literacy workshops for parents and caregivers.

The program aligns with state standards and assessments, but as its tagline goes: We don’t teach the reading, we teach the reader.

Ford expands on it: “We teach the reader to master the thinking parts of reading, and the skills so that they can read and make meaning with any text.”

Sam Ramos, a longtime training and program coordinator, talks about making meaning by drawing identity connections, so that we and our ancestors become living texts.

“Our stories are things that our children need to hear. From the small minutiae to the story of how we got here.”

Sankofa translates to “go back and get it.” That spirit of connection to the past and belonging permeates not just NdCAD’s literacy programs, but their office and tutoring space. “Welcome home,” every person is greeted upon entry.

Centering students aspirations, not skill gaps

A core tenet of NdCAD’s approach involves reframing how we think about student strengths and aspirations, particularly when building individual learning plans.

Sankofa tutors analyze robust pre-assessment data looking for student strengths. They don’t start with the skill gaps.

“Now you build an individual learning plan for you. What are you trying to learn from that child about the strength that they bring?” describes Ford.

“What are you intending to learn from the child about what turns that switch on? Because that’s what you need in order to introduce them to the skill areas that are not as strong.”

Transformative outcomes for students and families

Family members of Sankofa students are strongly encouraged to participate in Parent Power. Staff talked about a Parent Power graduate’s a-ha moment in a conversation about building identity connections.

100% of Sankofa students increase their reading skills and 65% finish the program meeting or exceeding grade level reading.

“Now I understand how in nine weeks my child went from ‘I can’t read and I don’t want to,’ to now I can’t stop them from reading and wanting to show off all the different phonograms they know.’”

NdCAD has the receipts: 100% of Sankofa students increase their reading skills and 65% finish the program meeting or exceeding grade level reading.

And it’s not just the kids. An evaluation by Ramsey County found that Parent Power was instrumental to improving families’ stability, well-being, and self-determination.

Ramos draws parallels between his young daughters and the scholars he has seen grow during his 15 years at NdCAD.

“They’re looking for the answers to those questions of why, especially at that age range of six through eight. Everything is why. ‘Why this? Why that? Why do I have to brush my teeth? Why do I have to do this?’ The why is so important,” Ramos explains. “But without the answers, they’re going to think it’s just another thing to do.”

“Understanding the importance of what [reading proficiency] means to them as individuals, as family members, as community members, as a people is why we see the gains that we see in our programs.”

Pushing expectations beyond the baseline

The READ Act compels schools to use culturally responsive instructional materials, though the provision seems likely to yield more cultural flavoring as opposed to the integrated approach proven successful by NdCAD.

While NdCAD uses highly culturally responsive materials, too, Ford believes teachers must be culturally responsive by recognizing who children are and where they come from. But he pushes them further.

“How does that translate into how you think about your instruction, how you think about what you hope to learn from the children and, most importantly, what you hope to learn about yourself from the delivery of your instruction?”

The READ Act sets new expectations; educators must determine how they will help students meet them. But Ford and Ramos urge us to aim higher than baseline standards and expectations. This comes back to reframing how we think about student strengths and aspirations.

“If we raise the standard and intrinsically motivate, they will meet the higher standard,” Ford says of students, before turning the spotlight back to the adults. “If we lower the standard, they will meet that as well.”

As schools implement the READ Act, we must teach kids to decode words. And, they must also learn how to decode the world in which they live. We adults must believe they can.