This post is part of a larger blog series this year, looking at how schools have used student-centered strategies to respond to the pandemic. This includes both learning designs, but also the success indicators schools use to know whether they are successful. Here, we profile Norris Academy in Mukwonago, WI.

Much of what gets showcased as educational innovation comes from urban areas—settings that don’t always offer a relevant blueprint for smaller, rural districts and schools.

That’s why we’re so eager to highlight Norris Academy in Mukwonago, Wisconsin. Norris is a one-school district where young people engage in learning experiences quite unlike those offered in most traditional districts.

Norris’ holistic approach views learning along four equally-important dimensions: wellness, academic, employability, and citizenship. Students find a home base within career-focused learning communities intended to refine and foster progress towards their post-secondary aspirations.

Students co-develop individualized learner profiles and pathways with the support of a wide learner network, a team of educators and support staff who collaborate closely to support their progress.

“Most of our kids have never experienced success” before coming to Norris, Executive Director Johnna Noll told us. Many were kicked out of their previous schools. About 25 percent are residents of a nearby treatment center for youth struggling with mental health issues, emotional behavioral disorders, substance abuse, and trauma. The traditional public education system failed to meet their needs. “When kids come to us, we know they’ve had all kinds of inequities and injustices in their lives… we have to accept that it’s happened to them, and help them figure out how to navigate it.”

Norris Academy At A Glance

Location: Mukwonago, WI (rural)

School Type: Single-school public school district

Grades served: 3-12

Number of students: 86

Students with Disabilities: 68%

English Learners: 0%

FRPL Eligible: 8%

Source: District enrollment data

Leveraging their multi-dimensional and competency-based learning framework, Norris staff work intentionally to engage previously disengaged and disenfranchised students—even in the face of a tremendous disruption like Covid-19.

Business as usual: Responding to Covid-19

In our conversations with Norris staff, we were surprised to hear them unanimously agree that the transition to distance learning was no big deal.

When schools closed in March 2020, the Norris School District already ran a virtual academy, a distance learning option that worked well for highly-mobile students and students who struggled with in-person settings. Systems previously developed to support both virtual and in-person learners—such as one-on-one “conferral” sessions scheduled using Google Calendar—would work just as well in an all-virtual format.

Over that first weekend, staff made sure all students had devices and hotspots, called every family, and added a Google Hangout link to the top of all students’ daily agendas so staff members could easily contact them. By Monday, staff were “live” with students by 8:30 a.m. “It was a relatively smooth transition,” Noll said.

Below we describe how staff at Norris leveraged two principles of student-centered learning, in particular—relevant, real-world learning experiences and competency-based progression—to keep students engaged and on track throughout, and in spite of, the pandemic.

Principle 1 in Practice: Making real-world connections to drive student learning

Norris staff motivate students to take charge of their education by providing learning experiences directly tied to their post-secondary goals.

When students enroll at Norris, they embark on a four- to six-week orientation and self-study process to clarify their career interests and goals. High school students then opt into a learning community—a group of students who share an interest in a particular career area (Business and Entrepreneurial, Human Services, Creative and Communication Arts, Skilled Trades, and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math [STEM]).

Learning communities are not only home bases for students, but are also fertile ground for career exploration. Students access a range of extended learning opportunities (ELOs), including career-focused learning visits, job shadowing, and internships. These experiences expose students to a range of fulfilling careers and foster progress along Norris’ employability learning dimension.

Covid has certainly impacted the kinds of ELOs students could partake in, something the Norris team struggled with last spring. But the school’s Employability Specialist worked over the summer to ensure students would have at least two to three ELOs per trimester in each learning community, at least one of which would have a virtual option. This year, ELOs included a trip to a hydroponics farm in Milwaukee and a visit to the local carpenter’s union to learn about apprenticeships.

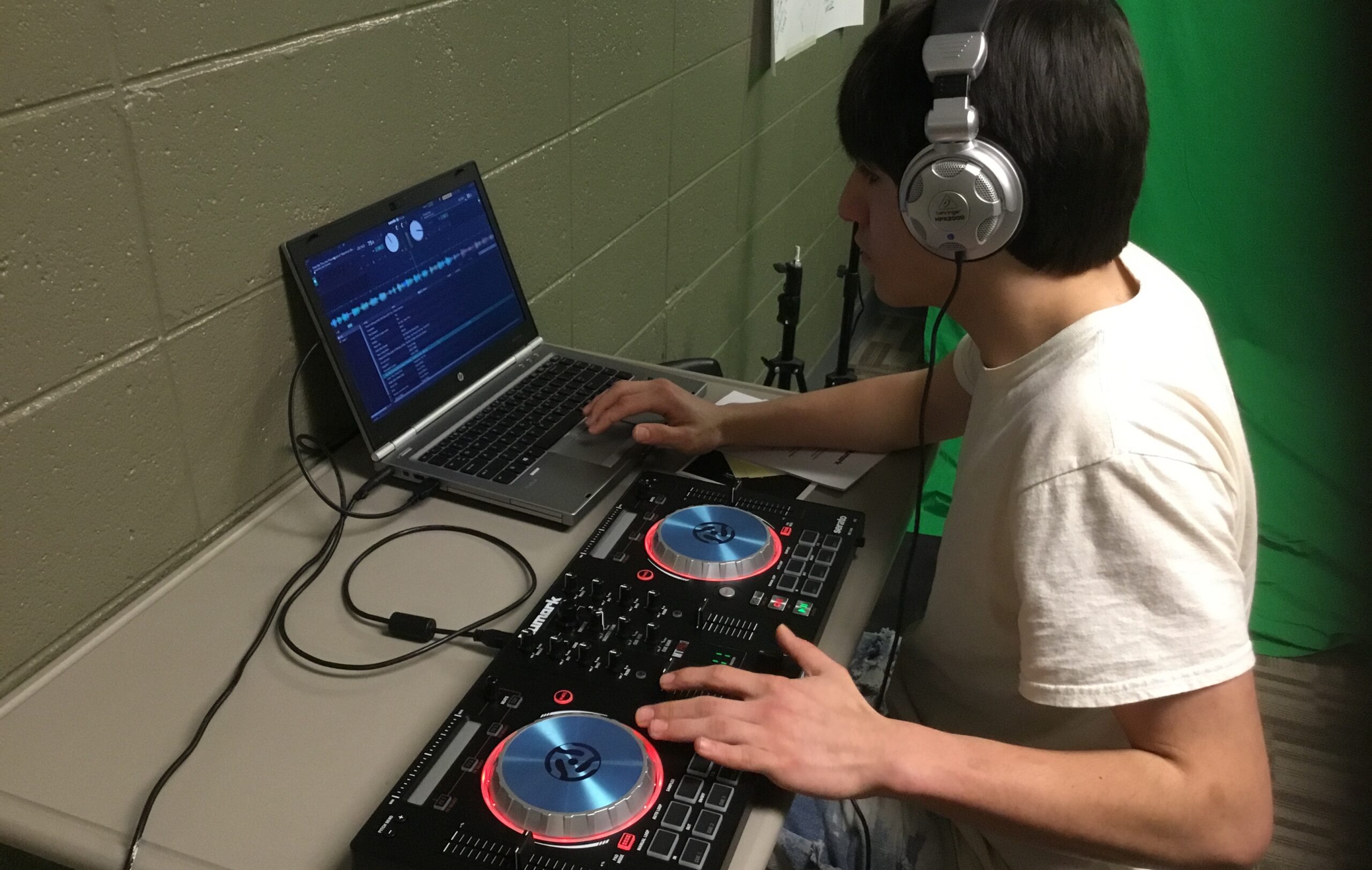

ELOs are not always group experiences. When one student expressed interest in becoming a DJ, the Employability Specialist found a local DJ who would mentor him. Regular meetings with his mentor inspired the student to develop a project plan to practice the skills he had been learning about. Together, they made a list of the recording equipment (mixing tables, etc.) he would need. The student submitted a purchase request and rationale—complete with Consumer Reports product reviews—which was granted by the Norris team.

Pandemic or not, there are important benefits to virtual ELOs, especially since the community around Norris is so small. For example, another student became passionate about astrophysics, but, as a Black youth, lamented the scarcity of Black role models in the field. According to Noll, the Engagement Specialist “dug and dug and dug,” eventually tracking down a Black astrophysicist at NASA who could connect with the student virtually.

“Schools have to be able to reach out,” Noll said, alluding to Norris’ commitment to finding just-right supports for their students. “They have to go beyond the walls of their schools and communities and look at the global resources that are available to them.”

Principle 1 in Evidence: Mapping and tracking learning in the “employability” dimension

Tracking a student’s progress along the employability dimension first requires a learner-specific plan and pathway that takes into account that student’s talents, interests, and career goals. During orientation, new students explore the different learning communities and complete a series of diagnostic assessments, interest surveys, and self-reflections, results of which are recorded in their dynamic learner profile.

At the end of orientation, students apply and interview for inclusion into the learning community that best reflects their career interests, then work with learning specialists to devise plans (goals) and pathways (experiences) for carrying out those plans.

As in the other three learning dimensions, the Norris team has developed a system to track students’ progress along the employability dimension in a series of Google spreadsheets linked to the learner profile. Students chart their mastery of specific learning goals in career-related “intro” courses or “work-based learning” courses (more on competency progression, below).

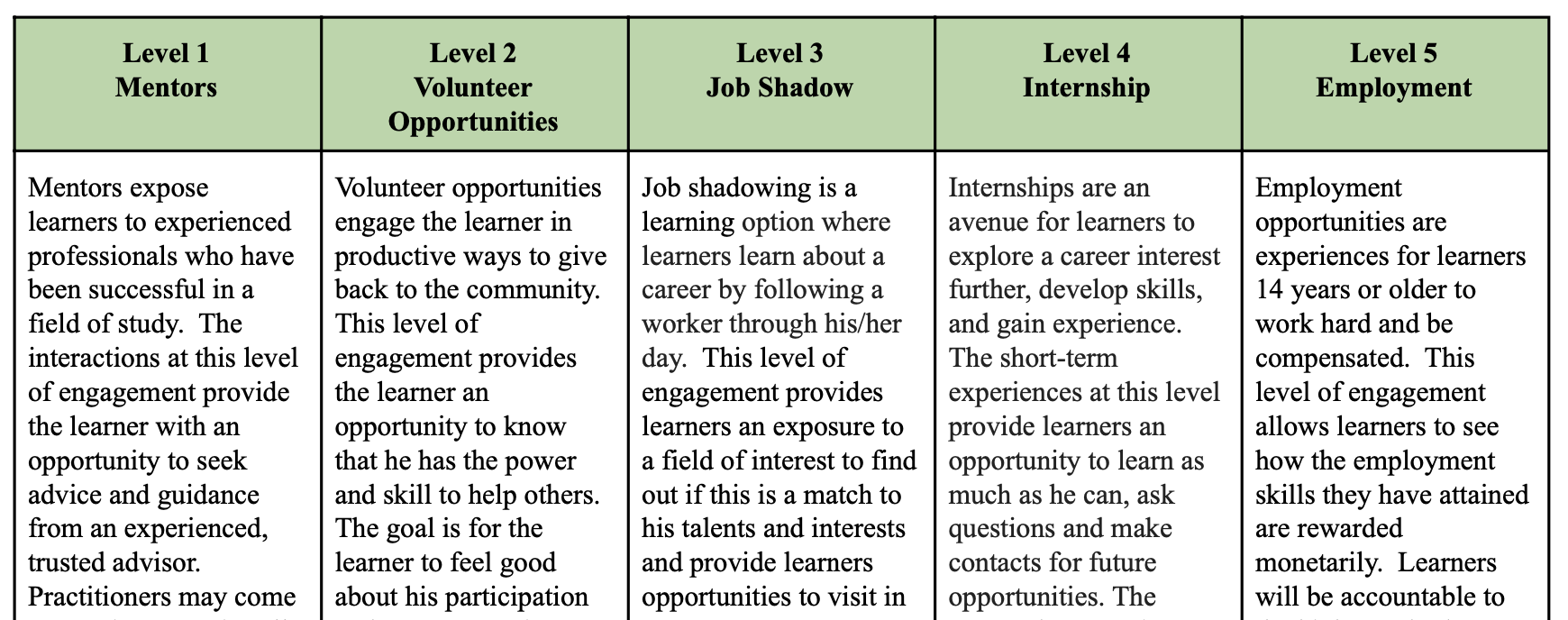

Depending on how long a student is enrolled, they progress through as many as five “levels of engagement” in career-focused learning experiences: mentorship, volunteer opportunities, job shadowing, internship, and employment. Along the way, they collect and track evidence in the form of resumes, cover letters, letters of recommendation, and applications to post-secondary educational institutions to document their progress and equip them with the skills and artifacts they’ll need to seek fulfilling work after high school.

Principle 2 in Practice: Mastering learning competencies at students’ own pace

Norris advances student-centered learning by charting students’ progress using a competency-based learning framework.

Like all public schools in Wisconsin, Norris is responsible for ensuring its students meet or exceed state standards in the core subject areas of math, language arts, science, and social studies. But unlike in a traditional school where students are shuffled from class to class and grade to grade on a predetermined and universal timeline, Norris takes as given that students progress at their own pace, receiving credit when they demonstrate mastery of academic content or skills rather than arbitrarily at the conclusion of a semester or school year.

What this means for students is that they don’t take traditional math or English “classes”—but instead work with learning specialists (licensed teachers) to select pathways specific to students’ learning styles, skill levels, and interests. For example, one student may thrive learning Algebra independently using an online math program; another may require more hands-on support and be invited to attend “Learning Labs” one to three times per week with small groups of students and a learning specialist.

When a student is ready to move on to more challenging content, they do. When they get stuck, they get help—learners can mark a pathway step as “Needs Help” and tag their specialist for on-demand “conferrals.” All students have access to learning coaches who help them troubleshoot barriers and activate other members of the learner network as needed.

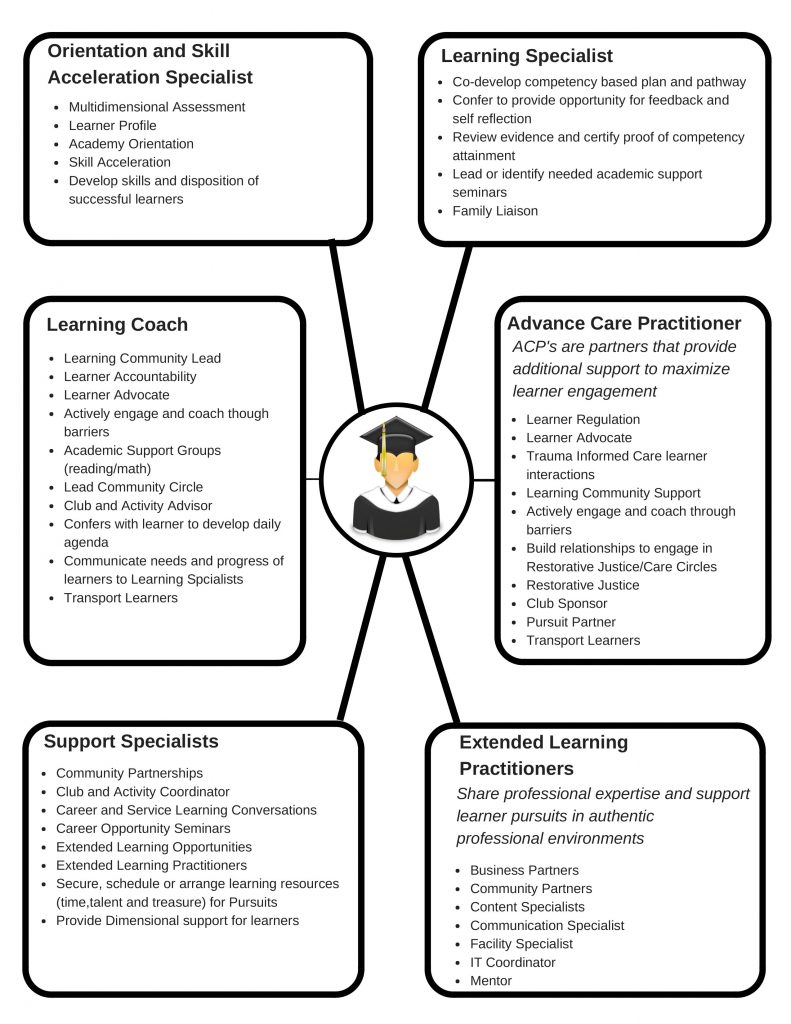

The Norris Academy “learner network”—the many adults who collaboratively support each student’s learning.

The Norris Academy “learner network”—the many adults who collaboratively support each student’s learning.While the transition to distance learning has meant that staff members—and learning coaches in particular—can’t keep tabs on students as easily as they had before, every student has a minimum of two daily check-ins with learning coaches to review their agenda and work plans, and discuss any challenges they’re encountering.

Principle 2 in Evidence: Documenting and monitoring competency progression

Graduating from Norris requires students to demonstrate mastery of learning competencies across all four learning dimensions. Each course that makes up a student’s Pathway to Graduation is divided into priority competencies, which are subdivided into learning goals.

Take high school Algebra: completing the course requires mastery of 5 priority competencies encompassing 48 different learning goals derived from the state math standards. Students must show that they have explored all 48 learning goals, and will earn one-quarter credit with each 17.5 percent of all priority competencies mastered. Depending on their post-secondary plans and specific career skills needed, learners choose to earn credit in various courses at level 2, 3, or 4 mastery; staff encourage level 3 mastery, which represents about three-quarters of the learning goals mastered per competency.

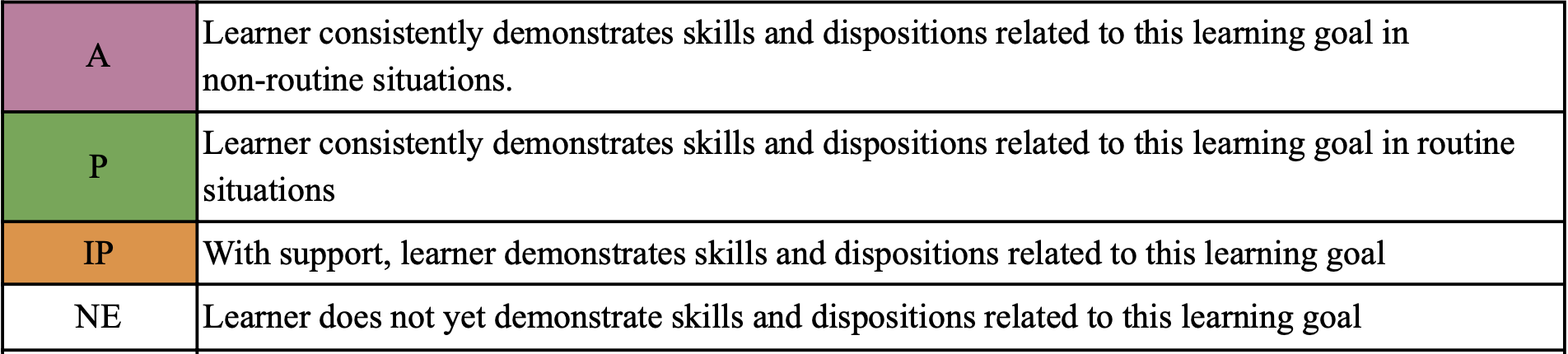

Formative proficiency level rubric, from Norris’ Pathways to Graduation Guide.

Formative proficiency level rubric, from Norris’ Pathways to Graduation Guide.As students progress through a course, they submit evidence on a regular basis, both formatively (to get feedback) and summatively (to demonstrate proficiency). “Evidence” can take on a number of forms, including written work, direct observation of concept mastery, student presentations of learning, or reports from online learning platforms or standardized tests. When a learning specialist sees that a student has submitted evidence, they review the evidence against a rubric and mark it as advanced, proficient, or in progress.

Though students are all on individualized pathways and have individualized Google dashboards for monitoring their own progress, staff maintain a schoolwide dashboard that aggregates a wide range of student data points and informs adjustments to the learning model. According to Paula Kaiser, Norris’ Director of Development, the staff is constantly striving to “get to the next best place” by examining schoolwide data and responding to the trends they identify.

Conclusion

Student and educator checking in on their in-classroom greenhouse

Student and educator checking in on their in-classroom greenhouseAt a surface level, the individualization of learning pathways at Norris Academy might seem to produce a school environment that is improvised and irregular, devoid of “economies of scale” that undergird learning model decisions in traditional school systems. However, behind the curtain, one finds at Norris an intricate and systematic orchestration of people and resources working harmoniously to support students’ learning.

The success of Norris’ model depends on airtight communication and collaboration between learning specialists, learning coaches, and the rest of the learner network. Several staff members referenced a common refrain at Norris: stay in your lane. It’s not a reprimand so much as a mantra reminding staff to “fulfill your unique role in the learning network so we can succeed as a team and meet the needs of each and every one of our learners,” as Kaiser put it.

In many communities, Covid has forced attention to the ways in which schools inadvertently but systematically sideline kids who need school the most. Districts have scrambled over the past year to track down disengaged students and align human resources to better address very real differences in students’ academic, social, and emotional needs. Such a shift has come at great cost to the educators and families most invested in students’ success.

But at Norris, an approach grounded in individual students’ needs was in place well before March 2020. According to Noll, “We are used to going that extra mile to connect with [students].” While Covid caused disruption at Norris as it did everywhere else, it was a bump in the road, not a seismic shift.