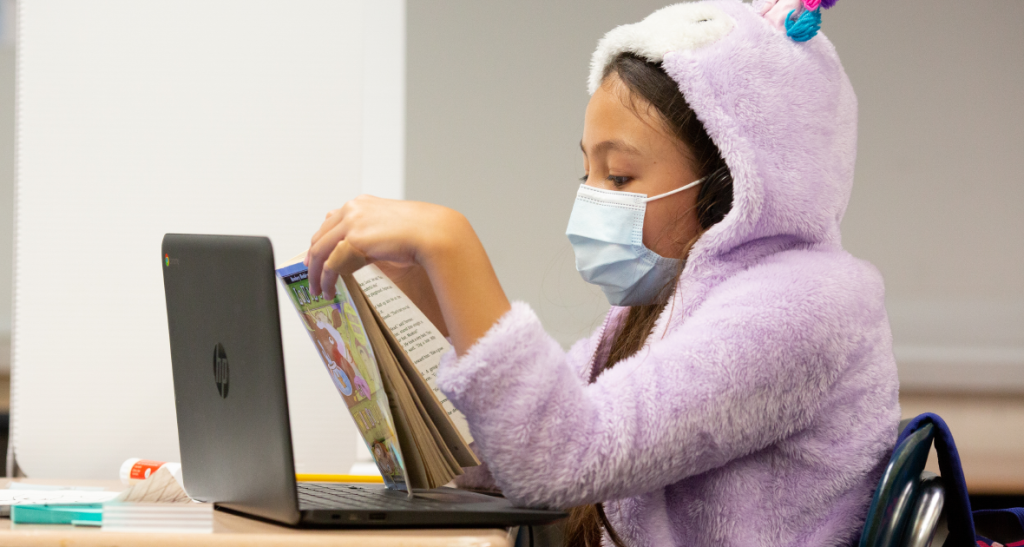

Photo by Allison Shelley for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action.

With Covid-19 surging across Minnesota, distance learning—the recommended model for nearly all of the state’s 87 counties—has become the norm for students. We wrote this summer that strong, caring relationships between students and adults were key to distance learning success.

With the conditions of the pandemic now worse, we asked: How are those relationships going? How is everyone navigating uncharted waters? In this post we focus on the roles of school counselors, psychologists, and social workers—those who operate in the realm of relationships and meeting students’ foundational needs—to find answers.

For staff, the job has changed. But that’s not a bad thing.

School mental health staff lament that often, in normal times, their role becomes consumed with behavior management. Reactive interventions instead of proactive support. Not this year.

At Academic Arts High School in West St. Paul, teacher-advisors developed personal growth plans with each student the first week of school. They asked students and parents, “What does your schedule look like? Are you working outside the home? Are you taking care of family? Do you have consistent internet access?” Questions taking into account the whole student, whose lives not just in school have been disrupted by the pandemic.

Early, honest check-ins establish a solid foundation for student-staff relationships.

“Normally, kids can get interrupted a lot,” shared Nicole Sobanski, a counselor at Meadowbrook Elementary in Golden Valley, citing the relative benefit of a virtual Google Meet to focus on the student in front of her, as opposed to meeting inside a bustling school building where privacy and space are scarce.

Students aren’t the only ones whose support looks different.

“We’ve done more training with our staff on self-regulation,” said Allison Litzenberg, a social worker at Parkway Montessori and Community Middle School in Saint Paul. “Helping teachers regulate themselves so they’re able to help dysregulated adults,” including parents and caregivers, in addition to students.

Kristin Lutz, a counselor and the testing coordinator at Alice Smith Elementary in Hopkins, said schools and districts cannot operate the same as before. That teachers need freedom to try new things, to hone in on what’s essential to students’ social-emotional health. “Adults need to rethink how we do things for kids,” Lutz asserted.

Isolated, many students are eager to return

Students are doing a remarkable job coping with uncertainty, according to those we spoke to. But it’s not easy. We’re seeing evidence of just how hard it is for students to engage right now. And virtual or phone assessments don’t give professionals the opportunity to pick up on nonverbal cues.

Students who have struggled with social anxiety have done relatively well. Those who thrive on social connectedness, not so much. For some students, distance learning is simply untenable.

“There are people learning a second language, people with dyslexia, people going into a foster home,” said Lutz. “It’s an equity [concern] for me right now. We’ve got to prioritize all those things.”

Hopkins Schools identified their most vulnerable students to keep receiving part-time, in-person instruction they sorely need while the rest of the district transitioned last month from a hybrid model to full distance learning.

Saint Paul Public Schools—which has been distance learning all year—kept open a center with precautions in place where students could safely go in-person to receive academic, technological, and social-emotional support from staff. With rising Covid numbers, the center has been temporarily shuttered.

Students are grieving the loss of normalcy in real-time. “When are we coming back?” they ask.

For staff, the only answer is the honest one: We don’t know.

Families are crucial partners

Many staff have engaged families nearly as much as students this year—establishing a partnership often lacking in the past.

“During in-person learning it becomes easy to allow families to fade into the background,” conceded Alex Leonard, Dean of Students at Patrick Henry High School in Minneapolis. “But during distance learning it is impossible to have even a slight chance of being successful without them.”

As with students, Leonard insists, transparent communication is key to these relationships. That includes acknowledging that the improvement many schools see in family engagement today is a result of failures to engage them in the past.

“[I’m] approaching parents on more of a human level. I’m right here with you in this storm that we’re trying to weather, I’m not here to judge you,” Sobanski said of her outreach to Meadowbrook parents and caregivers. “I’ve probably gotten to know some parents a lot better than ever before.”

A common tactic among those we spoke to: Home visits. Masked, outdoors, socially distanced, usually for only 15 minutes. Often with no agenda but to check on how families are doing.

In many cases, this means connecting with parents that schools were previously missing. There could be a barrier around transportation, or childcare, or work schedules. Home visits are a preferable alternative for many to meetings at school.

Staff report more evening meetings with families this year. And texting apps like Google Voice have been better able to elicit responses from families and students alike.

“The amount of partnering with parents that I’ve seen this year, I absolutely hope that it will continue,” said Litzenberg from Parkway Montessori, considering what practices deserve to keep after the pandemic ends.

A new paradigm is here to stay

The professionals we spoke to see promise in more proactive, social-emotional student support and new methods for engaging families. They also see new opportunities in how school is run.

The personalized growth plans at Academic Arts are likely to stick around. And the school is considering a permanent digital learning day—similar to this year’s hybrid schedules—to allow students the flexibility their lives might require.

“Schools are finding ways to improvise and still follow the laws and ethical guidelines,” said Ty Cody, school psychologist at Academic Arts. “We’re going to push the limits to do what we can to support kids.”

The future also holds challenges.

Educational disparities for historically underserved students have been exacerbated by the pandemic. The staff we spoke to are focused on mitigating the harm done, but they expect Covid slide to be a lasting legacy for many student groups.

The trauma of the public health crisis won’t abate overnight either. A return to the structure and stability in-person school can provide will help students be ready to learn like before. But it will take patience and grace, much like today.

The consensus is clear: Schools can’t go back to business as usual.

Nor should they.

Found this useful? Sign up to receive Education Evolving blog posts by email.