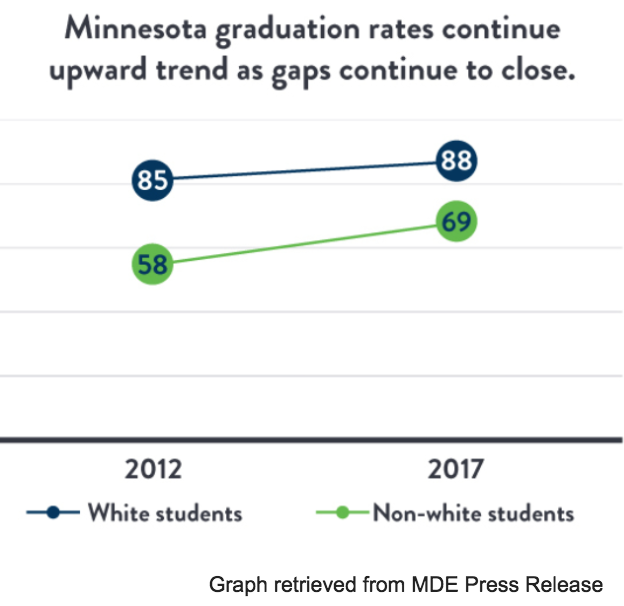

Last week, the Minnesota Department of Education (MDE) released the four-year graduation rates for the class of 2017, which reached a new statewide high of 82.7 percent overall. The statement also touted the narrowing of the graduation gap between white students and students of color. Specifically, in 2012, white students graduated at a rate 26.5 percentage points higher than students of color. The new 2017 data showed that the gap has been reduced to 18.7 percentage points.

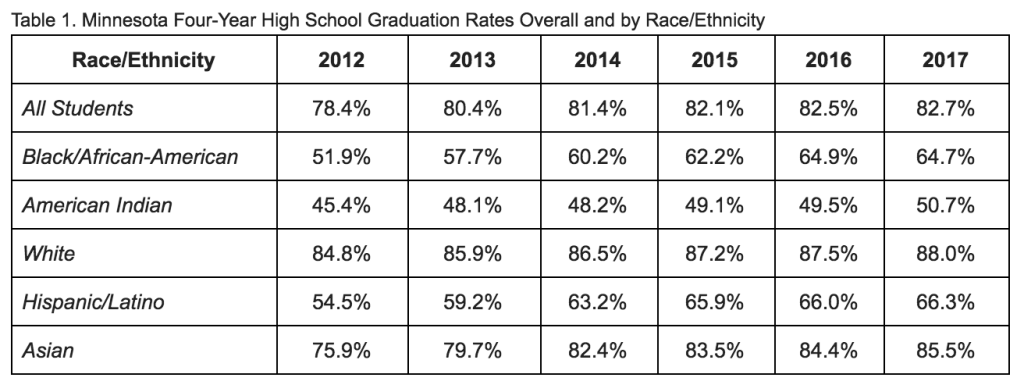

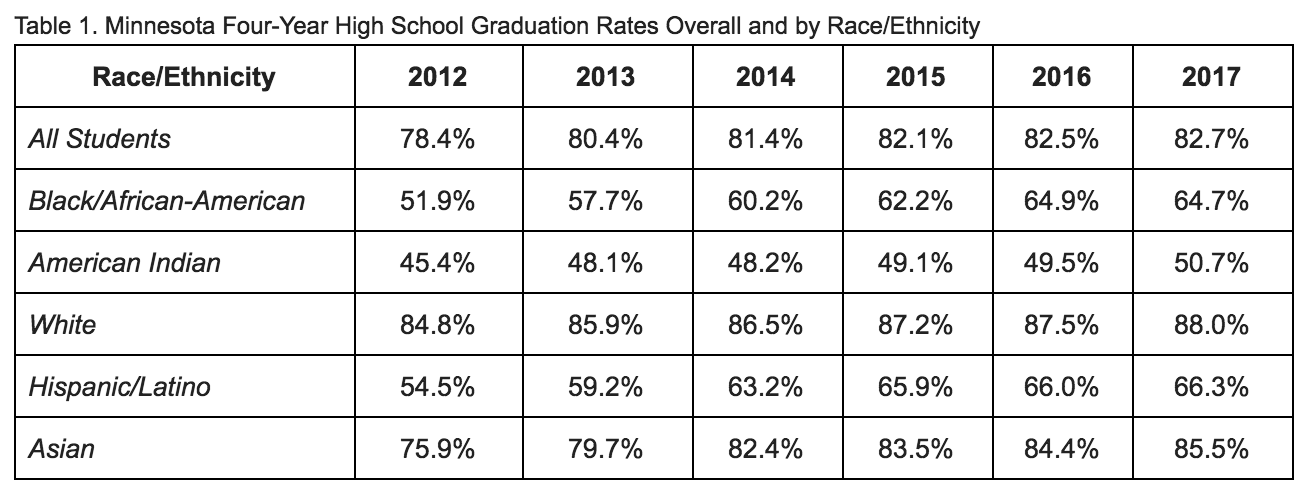

Digging deeper, Table 1 illustrates that graduation rates for African-American and Hispanic/Latino students have grown by over 12 percentage points from 2012-2017. During that same period of time, graduation rates for Asian students have grown by almost 10 percentage points and graduation rates for American Indian students have grown by 5 percentage points.

Time to Celebrate? Not So Fast.

Teachers, administrators, communities, and students definitely deserve acknowledgement for their accomplishments and efforts in raising graduation rates and closing the gap.

That said, when the graduation rates data is examined in conjunction with other data points—the percentage of students who met or exceeded standards on the Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments (MCAs) and ACT scores—the success story becomes more muddied and raises the question: Do increasing graduation rates mean more students are doing more rigorous and higher-level work that prepares them for college, career, and life?

MCA and ACT Scores Indicate There is Much More Work to Do

There are two major assessments—MCAs and ACT—used in Minnesota to gauge college readiness. The MCAs are the state assessments used to meet federal and state legislative requirements. According to MDE, if a student “Meets” or “Exceeds” standards on the MCAs then they are, “expected to be able to successfully complete credit-bearing coursework without the need for remediation at a two- or four-year college or university, or other credit-bearing postsecondary program.”

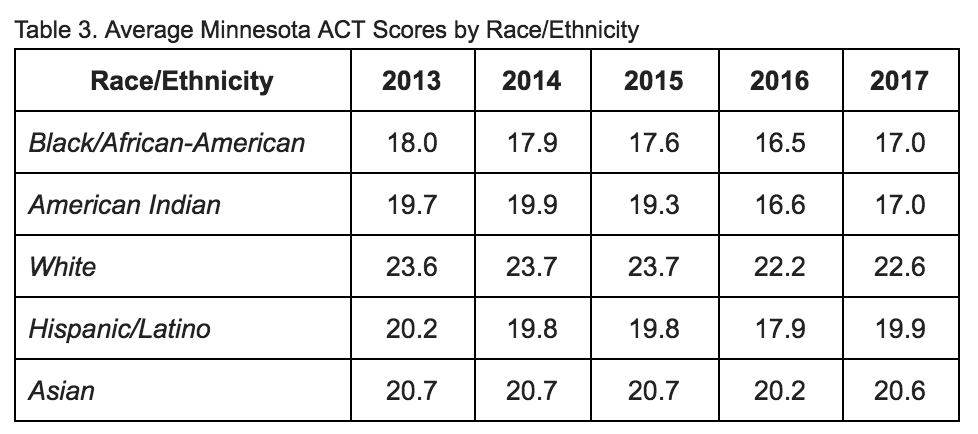

The ACT is a standardized, multiple choice assessment measured out of thirty-six points and covers four skill areas—English, mathematics, reading, and science. It’s been generally accepted that a composite score of 22 indicates college readiness. And, unlike the MCAs, the ACT is accepted at higher education institutions across the country for college admissions.

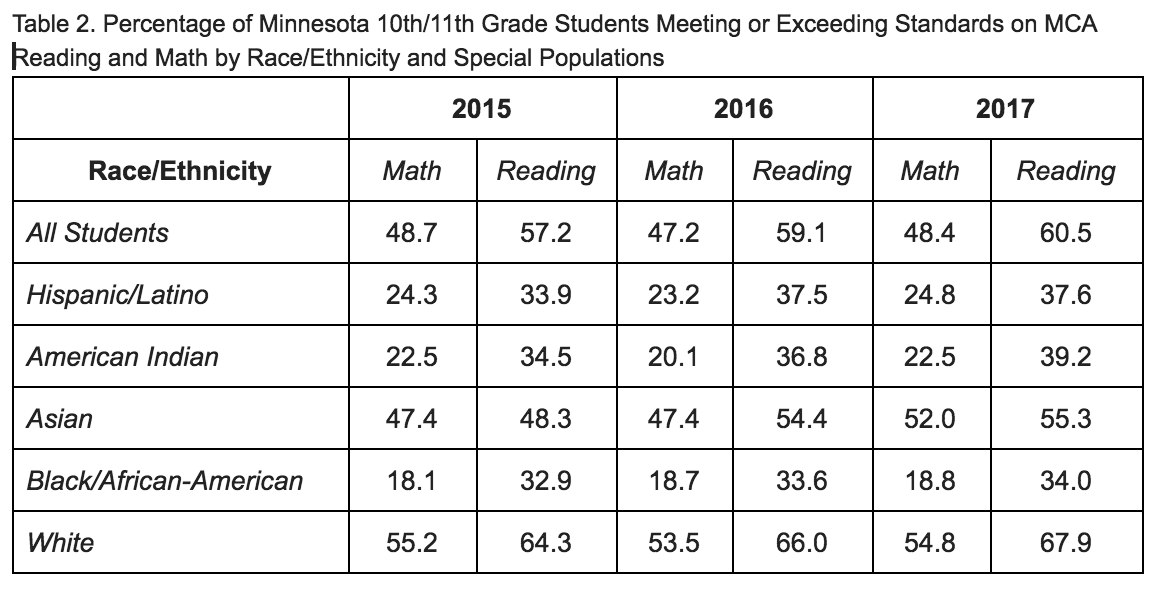

The data in Tables 2 and 3 indicates there is a lot of work to be done to ensure that all Minnesota students, but particularly students of color, are prepared for life after high school.

In 2017, the graduation rates for Black/African-American, Hispanic/Latino, and American Indian students was above 50 percent. However, in the same year for all three student groups, less than 40 percent “Met” or “Exceeded” standards on the reading MCAs, less than 25 percent “Met” or “Exceeded” standards on the Mathematics MCAs, and the average ACT score was several points below 22.

And while there are other factors to consider—MCA opt out rates and increase in students taking the ACT—comparing the MCA and ACT data to the graduation data raises the question: What other measures, beyond test scores and graduation rates, can be used to measure student readiness for college, career, and life?

It’s Time to Expand Measures of Readiness

The contradictions between the graduation rates and assessment scores present different narratives about the preparedness of Minnesota’s high school students. This dilemma is not limited to Minnesota. Rather, several states around the country—Illinois, California, Maryland, and DC (to name a few)—have faced similar questions about whether they are preparing their graduates for life after they leave high school.

In order to answer this question, there are a number of organizations, states, and schools across the country that have been examining how to measure school quality and student preparedness beyond a single standardized test score.

In order to learn about how innovative, student-centered district and charter schools in Minnesota measure success, this year Education Evolving will explore what “readiness” means for students entering college, career, and life in the 21st century. In particular, what competencies—skills, knowledge, and dispositions—have employers and society identified as important?

This project will culminate in a policy paper to be published in late 2018, along with a toolkit of possible measures and indicators that we’ve found schools are using.

Found this useful? Sign up to receive Education Evolving blog posts by email.