What would happen if schools had more autonomy and accountability for performance? And what if metro regions featured more diversity of school designs and parental choice?

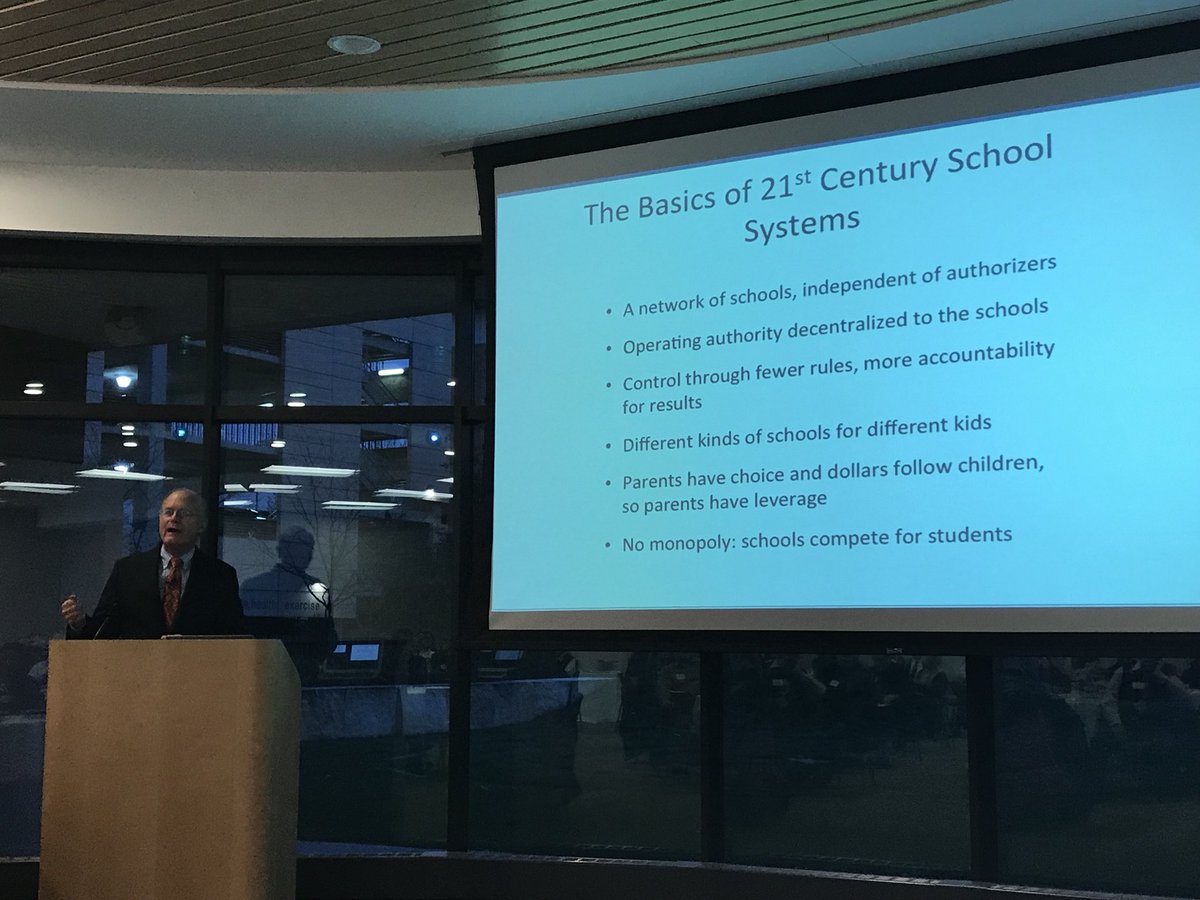

In his new book, Reinventing America’s Schools, David Osborne, the Director of the Reinventing America’s Schools Project at the Progressive Policy Institute, answers these questions by describing the transformational E-12 public education changes that are taking place in several American cities—including New Orleans, Denver, Memphis, Washington D.C., and Indianapolis—that have adopted these strategies, across both district and charter schools.

On Wednesday, as part of his 24-city national tour, Osborne presented the lessons and stories he has learned from those cities to over 80 educators, administrators, legislators, and organizational leaders at the Wilder Foundation in Saint Paul. The event was co-hosted by Education Evolving, EdAllies, and the Progressive Policy Institute.

The Need for Transformational Change in E-12 Public Education

In his introduction, Osborne described the need for a new model of E-12 public education. He asserted, “We all know our urban schools have struggled over the past few decades. And that’s no one’s fault…The problem is that they are trapped in a system that was designed over 100 years ago.”

Osborne explained that when our current, industrial education system was designed, it was set up to be stable and bureaucratic. However, it also disempowered teachers and Osborne noted, “we all know that you don’t get the best from people who feel disempowered.”

While our economy and industries have changed over the past 30 years, our system of public education has not. Rather, our schools have maintained the cookie cutter approach to educating students, which Osborne argued is incredibly unfair. He explained, “Kids have different needs and there should be a variety of school models so that parents can choose which schools are best for their students.”

During his talk Osborne shared lessons about how three cities featured in his book—New Orleans, Denver, and Indianapolis—have granted autonomy to schools and teachers to design schools that are more responsive to student needs. Those lessons and stories, along with student growth and achievement data, are discussed below.

New Orleans: Starting Over In the Wake of Katrina

The first city Osborne talked about was New Orleans. When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, the city had arguably the worst school system in the country. According to Osborne, “The student test scores were abysmal, it was corrupt, and it was bankrupt.” While disastrous, Hurricane Katrina created an opportunity for the state to recreate the city’s failing school system from scratch.

In November 2005, the Louisiana Legislature passed Act 35, which immediately transferred over all of New Orleans’ schools that were performing below the statewide average to the state-run Recovery School District, which would reopen them as charter schools. According to Osborne, over the past 12 years, New Orleans has seen some of the fastest growth in student proficiency, as well as graduation and college going rates in the country.

Specifically, before Katrina hit New Orleans, 60 percent of New Orleans students attended schools that were performing in the bottom 10 percent of the state. Now, only 10 percent of students attend such schools. Additionally, before Katrina, about half of New Orleans students dropped out of high school. Now, New Orleans boasts a graduation rate of 76 percent. Further, before Katrina fewer than 20 percent of New Orleans’ students went to college, as compared to 64 percent in 2016, which is higher than the statewide average.

These results are particularly impressive when New Orleans’ student demographics are taken into consideration—85 percent of New Orlean’s students qualify for free or reduced priced lunch and 82 percent are African-American. According to Osborne, “There is no other city in America that has these demographics and can do this.”

Denver: District Shifts from “Running” to “Overseeing” Schools

Osborne also discussed what has been taking place in Denver since 2005 when Michael Bennet became superintendent of Denver Public Schools (DPS). When Bennet took over DPS it was struggling. Almost a third of the seats were empty and almost 16,000 Denver students had left DPS for private or suburban schools. Additionally, DPS only graduated 46.8 percent of its students on-time in 2003 and the average percentage of students scoring proficient or advanced on the Colorado Student Assessment Program was far below the state average.

Since then, the district has tried several strategies to adopt the 21st century autonomy-for-accountability model Osborne describes in his book. Initially, DPS contracted with high performing charter schools in the city, and asked them to turn around failing district schools. In 2008, after the passage of Colorado’s Innovation Schools Act, DPS used the new “innovation school” designation to give some district schools (currently 58 in total) autonomy to develop new models to meet the needs of individual students. Most recently, in April 2016, the Denver school board approved four district schools to form an innovation zone, the Luminary Learning Network, overseen by a nonprofit organization.

Their efforts seem to be paying off. DPS’ graduation rates have increased from 39 percent in 2007 to 67 percent in 2016. In that same period, the number of students passing Advanced Placement exams has tripled, the average ACT score has increased by almost three points, and there has been a 15 percentage point increase in students scoring at or above grade level in reading, writing, and mathematics.

Indianapolis: An Innovation Network Within the District

Finally, Osborne discussed what has been happening in Indianapolis since 2014 when Indiana’s legislators passed legislation that enabled school districts across the state with the authority to create Innovation Network Schools (INS). The purpose of these schools is to allow the district, and schools within their district, additional flexibility to make decisions that are based on the needs of a school’s students.

Specifically, INS schools have increased authority and autonomy to make decisions about all aspects of their school—both academic and operational. In return, those schools are held accountable by the district for agreed upon student outcomes. INS schools are run by nonprofit organizations who have their own boards, have 5-7 year performance agreements with the district, are given district buildings, and are considered to be part of the district. In Indianapolis Public Schools, there are four pathways a school may take to become an innovation school.

The preliminary results from INS are promising. Specifically, INS schools are the fastest improving schools in Indianapolis. Osborne noted that about 10 cities around the country are employing this model, including Camden, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Atlanta.

Could This Happen in Minnesota?

After the talk, Osborne served on a panel with local education leaders who discussed how the performance-based contract model could become more prominent in Minnesota. The panelists were:

- Brandie Burris-Gallagher, Policy Director, EdAllies

- Rep. Roz Peterson (56B), Minnesota House of Representatives

- Julene Oxton, Innovation Coordinator, Lakeville Public Schools

During the panel, Oxton asserted that the choice aspect of Osborne’s talk resonated most with her and her experience in Lakeville. She explained, “Even suburban and rural families want choice…Even if the schools aren’t ‘failing’ it is still important for us to think about the students” and how they can increase competition. She noted that, within Lakeville, they are creating competition and that, even though there has been some tension, she believes it has made the district better.

Another component of the talk that resonated with the panelists was the increased school autonomy for increased accountability. Burris-Gallagher contended that, from the interviews and focus groups she and her organization have done, parents and families could be some of the strongest supporters of school autonomy because, under the traditional model, there are very limited opportunities for them to be meaningfully involved. Oxton also noted that, from prior research done by Education Evolving, we know that the public trusts teachers and would support them making more decisions in schools.

Rep. Peterson commented, based on her prior experience serving on a district school board, that sometimes granting autonomy to schools in a district setting can be complicated. Letting some schools do things differently can be seen as “giving them special privileges”. It’s really, she said, about changing a district culture from one of sameness and equality, to personalization and equity.

The Twin Cities were the 14th stop on Osborne’s book tour, and he has 10 more to go. Up next, David heads to Chicago early next week. Read more about David’s book or order yourself a copy on the Reinventing America’s Schools website.

Found this useful? Sign up to receive Education Evolving blog posts by email.